History in Fragments

Madera, 23

Sabrina Amrani is pleased to present History in Fragments, a group exhibition curated by Babak Golkar for APERTURA Madrid Gallery Weekend 2022.

History in Fragments is a group exhibition featuring works of artists whose practices touch on aspects and qualities of ceramics, either as a primary material, conceptual framework or context for larger installations. This exhibition highlights the diversity of approach to making artworks in ceramics and the significance of this media as a recorder of time and witness of events.

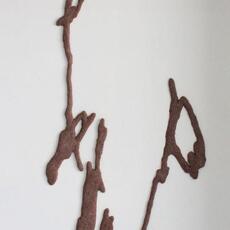

History in Fragments will showcase works in ceramics by the gallery artists Manal AlDowayan, Joël Andrianomearisoa, Gabriela Bettini, Luis Úrculo, Julia Llerena, Edison Peñafiel and Timo Nasseri.

Clay is one of the oldest materials humans have used to make objects and ceramics is one of the most ancient industries we have created. Venus of Dolní Věstonice is the oldest known ceramic artifact, dated as early as 28,000 BCE, during the late Paleolithic period. The first examples of pottery appeared in Eastern Asia around 18,000 BCE. We know these through fragments that have survived for thousands of years. Historically, depiction and surface treatment on ceramic vessels have been a way to tell stories and record histories. Numerous examples of these works have survived from ancient Greece, Rome, Persia, China, South America, Africa and North American and Australian Indegenous cultures. Since the early days of industrialization ceramics surfaces have been exploited in the service of marketing a signature look, such as found in Delft porcelain in the 17th Century and British and French porcelain manufacturing from the 18th century. In the late 19th and early 20th century there have been attempts to experiment with ceramics, mostly through the modernist motto of “form follows function”.

Up until the 1960’s there have been very few instances of ceramics being considered as a material for making art and there had been major challenges of the media being considered in the critical realms of visual culture. In the past two decades, however, ceramics has made its way into mainstream contemporary art by ways of making the medium breaking away from traditional form, function, glaze and surface decorations, and pushing it into performative acts, video works and large installations. This historical shift is significant in at least two ways: 1) ceramics can, finally, enjoy success in a wider context as the art market seems to have found a new way of asserting this ignored medium and putting it under the spotlight 2) and perhaps more significantly, now ceramics can deservedly exercise some of its historically critical roles (such as recording histories) parallel to strong conceptual ideas, while not being bound to any physical and mediumistic restrictions.

The main curatorial direction behind History in Fragments is to engage with form and function in ceramics. However, these notions could benefit from some unpacking. What is meant here by form is not shapes and volumes at the service of design, but forms that are unexpectedly materialized in ceramics and are harmoniously reflective of our times–those that are capturing the depth of our conditioning, individual and collective suffering. What is also observed through the notion of function is not holding a liquid, green salad or cooked rice. On the contrary, the exhibition intends to highlight those functions that are manifestations and extensions of the artists’ conceptual thinking.

In a series of paper-thin rolled porcelain works, entitled Just Paper (2018), the Saudi artist Manal Al Dowayan, subtly, subliminally and delicately critiques the notion of “property” and “ownership” in relation to gender and body. She examines the imagery and titles used on the covers of books written by (clergy)men for women: books that claim to help guide women as they exit their private spaces and enter a public sphere that, according to the authors, belongs to men. The porcelain papers are reproductions of the content of the mentioned religious books, printed on porcelain to give them a permanent, but delicate existence. Just Paper (2018), highlights the fragility of the words they hold. Unassumingly simple in form, once the surface decoration is revealed the work becomes extremely potent and critically significant.

Notorious for its fragility, it is shocking that works made in ceramics have survived, witnessed, documented and retold histories for millennia. Contrary to the common belief, and with much irony, a piece of ceramic can be preserved with much more ease than say a painting. It is where we put the value in a work of art that all of a sudden a broken piece of ceramics has less value than an unbroken one (or no value at all). In fact the Japanese Kintsugi technique of mending broken pieces of ceramics with gold, points to this very problem of valuation. A case in example is a series by Julia Llerena called Frágil (2019) in which she mends fragments of broken porcelain and glass together, making renewed collaged objects that carry contexts from both ceramics and glass.

Joël Andrianomearisoa has used ceramics in a slightly different way. Known for his large textile ensembles made out of smaller fragments of fabric, Andrianomearisoa has been working with other ready-made objects and modified them to create new artworks since the beginning of the pandemic. I have no regrets for the past and this is not the end of the world (2022) is an assemblage of eclectic colonial porcelain plates that the artist has purchased from different flea markets in Madagascar, breaking some of them and painting portions of them in his signature color: black. What is intriguing about this installation is the strategic choice of the artist using “traditionally'' functional ready-made objects made for everyday utilitarian use and rendering them dysfunctional by recontextualizing them in the installation. However, by doing this simple act of recontextualization, Andrianomearisoa opens a larger reading of these seemingly innocent objects, pointing at certain histories at play, particularly Imperialism and Colonialism, while leading us through that journey through his poetic title.

The artists Gabriela Bettini and Edison Peñafiel have been invited to produce works in ceramics for the very first time. The results demonstrate how artists of great conceptual thinking are able to work with ceramics and produce works that are within the language of their respective practices, yet extend beyond the confining genealogy of ceramics. Likewise, Timo Nasseri and Luis Úrculo, who lead conceptually-driven art practices, independent of specific media, have recently been making works with particular attention to ceramics as a medium. This is the first time these artists will be publicly showcasing these works.

There are many other threads that can be traced between the selected artists and their practices. What is at the core of History in Fragments is the notion of fragment and the significance of fragmentation in constructing histories. It is so significant that they all use fragmentation as a strategy, form, method or context to produce works. History in Fragments aims to trigger some questions: Is fragmentation, in fact, not the most liberating way of viewing history? and perhaps the most genuine and accurate method for understanding it? Not through one voice and narrative, but fragments of many voices and gestures? And, isn’t clay, still, one of the most reliable and relatable media to produce works that records history?

August 2022

Babak Golkar